Tatiana’s* voice is almost inaudible as she relates what happened to her in Bambari, in Central African Republic, three months ago.

“My husband was killed by armed men, and I was taken prisoner. In their camp, the men raped me. I was held there for several days. I lost one of my children there in the camp, and a short while after I managed to send the other child out of the camp to buy something. I finally managed to flee.”

The tip of the iceberg

Tatiana’s story is not an isolated one. Since it opened in December 2017, nearly 800 patients have been treated at MSF’s sexual violence clinic in the Hopital Communautaire in Bangui, the country’s capital. Most of the patients visiting the clinic are women, and a quarter of them are under the age of 18

Across all of our projects in Central African Republic, we treated 1,914 victims of sexual violence in the first six months of 2018 alone, the vast majority of whom were seen in clinics and hospitals in Bangui. This stream of patients provides a glimpse into the huge level of need in a country riven by conflict, and lacking both reliable healthcare and a functioning judicial system.

My husband was killed by armed men, and I was taken prisoner. In their camp, the men raped me. I was held there for several daysTatiana, victim of sexual violence in Bambari, CAR

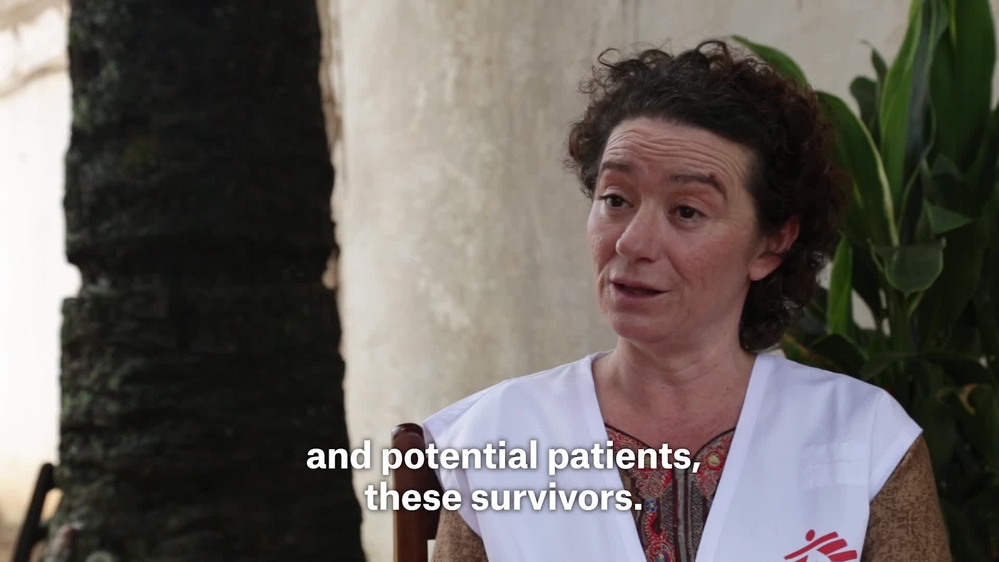

The topic of sexual violence may be rarely broached in public, but Susi Vicente, Coordinator of the Sexual Violence Project in Bangui, confirms that there are plenty of prospective patients.

“It’s clear that the number of people who see us only represent the tip of the iceberg. We know that there’s a problem, and that the population need to know that treatment and help are available. Once people hear that free medical services are available, they are eager to seek treatment.”

Sexual Violence in Bangui – Project Coordinator Interview – EN

Rape as weapon of war

The widespread use of sexual violence as a weapon of war in Central African Republic has been well documented: in 2017, Human Rights Watch found that armed groups routinely used rape and sexual slavery as a tactic of war over a five-year period between early 2013 and mid-2017 .

This recent history bodes ill for civilians currently facing another escalation of violence in the country. In the first half of 2018, there were renewed outbreaks of violence in numerous pockets across the country. Bambari, a town previously lauded as the ‘weapons-free city’, descended once again into conflict in April this year and giving rise to cases like Tatiana’s.

But though many women experience sexual violence as a direct result of the conflict, it is not the only culprit. While the dangers are greater whenever there is fighting, the general absence of safeguards and mechanisms to protect those at risk is also responsible, creating a worrying environment for women and children who have little recourse to justice in the event of an attack.

“If someone comes and says that her stepfather is attacking her, or a cousin, there is no system in place that guarantees them a safe refuge and it may be willfully ignored by the victim´s family”, says Susi. “Many of our cases are related to domestic abuse by a family member or someone in the community.”

Help to recover

The availability of midwives, doctors, and psychologists at the clinic enables patients to receive check-ups for both physical and mental health. If a patient arrives within the crucial 72-hour window following an attack, doctors are able to prescribe post-exposure prophylaxis, which can prevent HIV infection. Crucially, MSF psychologists can work with patients over the longer term to help them begin to rebuild their lives following a sexual assault.

For Tatiana, life is slowly improving. Now, she is living with her brother and his family and helping her sister-in-law in her daily work. But such severe trauma is not easily forgotten, and the memories simmer just below the surface.

“At the beginning it wasn’t easy for me. Since I started the treatment here, and after talking to the counsellor a lot, I feel a bit better compared to the beginning. But it’s not easy either. It’s not easy at all.”

*Name changed to protect identity