No statistics on sexual violence provide a complete picture of the problem or its prevalence. Shame, fear, stigmatisation and many other obstacles prevent an unknown number of victims from receiving, or even seeking, treatment. And yet getting immediate medical care after sexual assault is critical in order to limit the potential consequences. In 2023, our teams treated over 62,200 victims of sexual violence; 22,300 more than the year before.

Quick facts about sexual violence

Post-exposure prophylaxis is given to victims of rape within 72 hours to prevent HIV in case of exposure. Emergency contraception should also be given promptly to be most effective. Antibiotics are given to prevent sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis and gonorrhoea, and vaccinations for tetanus and hepatitis B. The treatment of physical injuries, and psychological support are also part of the package of care.

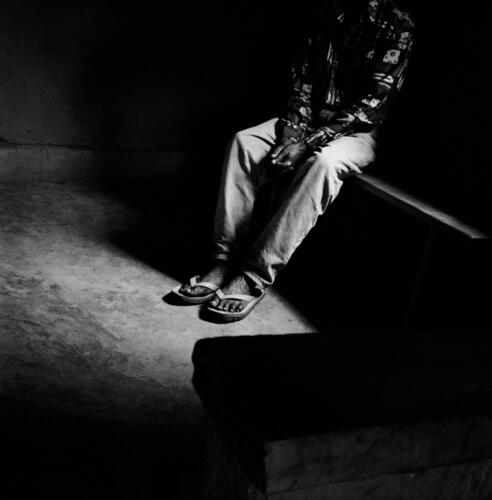

Sexual violence against men and boys includes rape, sexual torture and sexual slavery. Men and boys are even less likely to report sexual violence than women for fear of stigmatisation and because of the enormous taboo around the topic. As a result, sexual violence committed against men remains particularly invisible and under-reported, and how to adequately meet the needs of male victims poses a particular challenge for us.

Rape and other forms of sexual violence are often widespread in conflict settings, where they can be used to humiliate, punish, control, injure, inflict fear, and destroy communities. They may also be used to reward or remunerate combatants, to motivate the troops. But millions of people living in stable contexts are also affected by sexual violence. In these cases, the perpetrators are often acquaintances or family members of the victims.

Medical care is crucial in the 72 hours following rape to prevent the transmission of HIV and an unwanted pregnancy. Stigma, fear of the aggressor and of others finding out are some of the reasons victims may hesitate to seek care and often do not pursue follow-up care. The prevention and management of unwanted pregnancy is often their biggest concern, and is part of the care MSF provides. Emergency contraception is allowed in almost all countries; however, termination of pregnancy is – for a variety of reasons – more complicated.

Collecting data on sexual violence: what do we need to know? The case of MSF in the Democratic Republic of Congo

A comprehensive response to family and sexual violence is critical

Epidemic of family violence in PNG requires a coordinated response

Medical Care Under Fire - Interview with Francoise Duroch

Reaching more survivors of family and sexual violence

Their dignity has been deeply wounded

Sexual violence rife in Goma camps

Ethnic violence in Masisi limits access to treatment

Victims of sexual violence must not suffer in silence

Research & Analysis

Critical gaps in mental healthcare for survivors of sexual violence

‘No one was left’ - Death and Violence Against the Rohingya

Against their will: New report on sexual violence

Sexual violence in platinum mining belt a major driver of HIV

Return to Abuser

Care for victims of sexual violence, an organisation pushed to its limits: The case of MSF

Collecting data on sexual violence: what do we need to know? The case of MSF in the Democratic Republic of Congo

MSF denounces the sexual violence against migrants travelling to Europe

MSF Field Research

We produce important research based on our field experience. So far, we have published articles in over 100 peer-reviewed journals. These articles have often changed clinical practice and have been used for humanitarian advocacy. All of these articles can be found on our dedicated Field Research website.

Visit site